This is neither a reasoned political argument nor a tourist post. Some context: I moved to Seoul in the summer of 2012 and set about finding academic work. I didn’t find any and spent 8 months sliding into debt. Finally I took a job writing in the ESL industry, which as I’ve detailed in far too many posts here, is the worst job I’ve held for nearly 20 years, (working in a factory making plastic sports equipment was worse, admittedly). My expectations of beginning a new life and starting work in my field have not been met, yet I’ve been too busy to chart an alternate course. I’ve booked a few days off over the holidays to slow down and think about where I might go from here.

To be clear, there are many aspects of life in Seoul that I enjoy. There’s my relationship with a wonderful woman, the friends both Korean and international I’ve made here, and the inspiring activists I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know. What inspires me is the people: Koreans have been friendly and welcoming to me from the beginning.

However, other parts of life in Korea have been more difficult for me. I’ve resisted blogging about the hard-right government, the pollution, the lack of vegetarian options, the impossibility of cycling, the intense work ethic, conservative and patriarchal values, etc. It’s not out of a liberal reluctance to criticize my hosts – I’d have no problem with Koreans coming to the country I was born in and finding fault – but because it quickly turns into a project on comparative nationalisms, of the go back to Russia variety.

The content of my complaints isn’t important: what’s changed is my attitude towards it. When I first got here, for example, I thought the way drunk older men would expect me to say, “Korea is #1!” was quaint, a holdover of the wounded pride that’s a legacy of Japanese and American colonialism. However, my terrible job and lack of prospects have turned cultural artefacts into irritants. I don’t want to become one of those internationals who separates himself as much as possible from his host culture, and ends up hating a place in which a lot of people go out of their way to accommodate strangers. That’s neither healthy nor respectful. So, I need to find a way to climb out of my rut. The first task is figuring out how I got here.

Academic

Part of the problem is that Korean university jobs are very hard to find. Despite there being dozens of universities, there are no central jobs site like the Chronicle of Higher Education. Or, to be fair, there’s one in Korean, but not in English – despite English university instruction being mandatory. Sometimes English jobs are advertised solely in Korean. The sure way to find university jobs in Korean is to visit each university’s website and check their jobs board; however, these websites are usually poorly designed and translated, and often only work in Internet Explorer. Plus it’s not practical to survey dozens of websites regularly, looking for jobs that may or may not exist. As my Korean friend told me, the Korean government doesn’t actually want foreigners in Korea: they’re a necessary evil, so no one’s going to make it easy for them to work here.

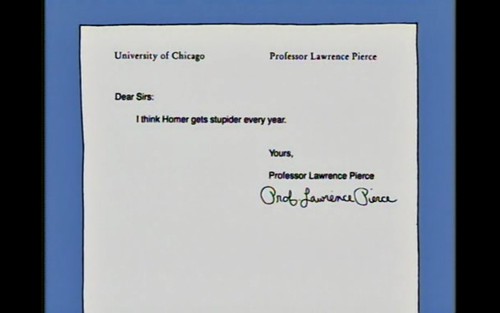

If I’m lucky enough to find a job listed, it’s in politics, which is a conservative discipline. Disciplinary boundaries are quite rigid in Korea, which means that my being ‘interdisciplinary’ is not a selling point. Universities want someone to research and teach elections, post-communism, comparative state systems – all topics lying nicely within the bounds of bourgeois politics. They don’t want to hear about revolutionary theory or practice, nor do they want socialist interpretations of bourgeois politics. It’s funny to me that the American right thinks academia is the preserve of radical leftists. They needn’t worry: the inbuilt bias of academia, towards scrutinizing rather than strategizing, keeps out most radicalism. Of course, some of the best socialists I know are professors, but 99.9% of professors remain non- or anti-socialist, and they tend to dominate hiring commitees.

So there are two problems: the discipline of the profession itself, and the lack of that discipline in my own work. When I research, I’m interested in strategic questions about capitalism and social movements. That’s tangential to a profession which has the goal of problematizing and critiquing. I had the same problem in all my university classes: we never got to the interesting ‘what do we do?’ questions. We just observed. Now that I’ve graduated, I’ve learned quickly that however good my research and writing skills are, they’re in the wrong paradigm. And switching paradigms feels impossible. I can’t base my work on premises that I consider dishonest. Or I can, but it takes a lot out of me.

The narrow range of acceptable bourgeois discourse

Activist

By now I sound like a dyed-in-the-wool activist, too angry and rebellious for the system to contain me. But that’s not it at all. Plenty of my grad school and professorial colleagues were better activists than me. I was neither a rabble-rousing student nor devoted to groups and parties. I’m actually OK with the boring, administrative tasks of social movement-building, it’s very close to the boring administrative tasks of wage-labour. But the complex political negotiations involved in coalition-building, the ego management, the confrontations – I’m not good at those. I prefer to study and write and occasionally debate, but not fight in the streets or the meeting room. I’ve known for years that I don’t have a future as an activist leader.

That leaves me in a difficult spot: too activist to be a proper academic, to academic to be an activist. The perfect place for me would be in a party school, like the German Social Democratic Party had prior to World War 1. Today? I feel like I have a few, not-very-appealing options:

1) Stay in Korea and keep applying to universities. That means writing research proposals and cover letters after my office job. It’s not ideal, and the longer I go without proper academic work, the less chance I have of getting hired. It also gives me the sensation of banging my head against a brick wall. I’ve been sending out applications to posts I could fill for three years. When does persistence turn into a refusal to face reality? Moreover, this presumes keeping my office job. I’ve proved that I can handle six months of the latter – that in itself is an accomplishment, given that when I started, I thought I’d last a week. So, presumably I can handle another six months. But do I want to move up a trouser size, see my waistline expand further and compensate for my lack of sleep with wrinkle cream? (Not to knock good cosmetics: having a salary has enabled me to take advantage of them. Proof: I know that the proper order is toner, serum and moisturizer. But they don’t deal with work, the root cause of bad skin.)

2) Find another job in Korea and keep applying for universities. This is less obvious than it seems. It’s illegal for me to work part-time. The only full-time work available to expats is teaching English in private schools, and I think care-taking a bunch of six year olds would wear me out faster than office work. There are plenty of part-time contracts available, editing or teaching business English, but those are illegal. I’m too old to be an illegal migrant. I live in hope that my networking will pay off: for example, I’ve been offered research and teaching, and I’m grateful for both. But to do them legally (and to pay my rent), they have to be on top of my full-time job. And that’s killing me.

3) Quit my job, go back home and apply for university jobs. I left home because there were no job opportunities. I could teach adjunct, it’s true, but that would require picking up courses at far-flung campuses, making less than I made as a secretary. All for the faint hope that I might find a full-time position in a small town in a country I don’t want to live in anyway.

If I went back home, I could also begin the transition to a different career entirely. But to what? It’s very hard to get into NGO work: the networking and experience requirements are even more onerous than in academia. I’m a good writer, but there are dozens of good writers selling themselves very cheaply online. I’m only going to couchsurf again if I have something more tangible than ‘starting over’ as a reward.

This is the conclusion that I’ve been using fatigue at work, catching up on sleep, getting drunk, windowshopping, etc. to avoid: there is no conclusion. I have precise, analytical language to pinpoint exactly why I’m fucked. I understand how the confluence of neoliberal austerity, being political, and being underqualified for academia and overqualified for everything else makes me fucked. But I don’t know what to do about it. My circumstances are largely beyond my control, and all the Buddhist acceptance of ‘the moment’ doesn’t change that. Yet I can’t shut off that critical part of my brain that says life is more interesting and important than ESL. I’m not prepared to give up; I’ll fight. But what do I fight?